Who were the Magi in the Bible?

The connection between Jesus and the True Religion of the mystics.

Cultural icons

The Magi are an inseparable part of our cultural celebrations of Christmas, ever present in nativities, carols, and pageants.

And whether you believe the visit of the Magi actually occurred, or you view the story as parabolic legend, there must’ve been a reason the author of Matthew included it in his Jesus origin story. In this post we’ll explore why having a better understanding of who the Magi were in the First Century can inform how we might approach our own faith today.

Who were they?

Many popular beliefs we hold today about the Magi aren’t actually found in the Bible, such as:

-They were kings.

-There were three of them.

-Their names were Balthasar, Caspar, and Melchior1.

Matthew says nothing about “kings” or how many were part of their group. The original Greek word used to describe these visitors is Magoi, which can mean a few things: sorcerer, magician, or astrologer. (Wow, I like these guys already.) And while there’s no mention of “wise men” in the list above, there’s good reason why this phrase has become such a part of our Christmas culture.

Magoi was first translated as “wise men” for the earliest English editions of the Bible produced in the 16th and 17th centuries. And there may be some merit to this description if we consider that in the book of Daniel, which the author of Matthew was very aware of and references several times, the Magoi seem to be a subset of a larger group of Sophoi, or “wise people.” It was much more recently, in the 1970s, that translations began to anglicize Magoi to simply read as Magi.2

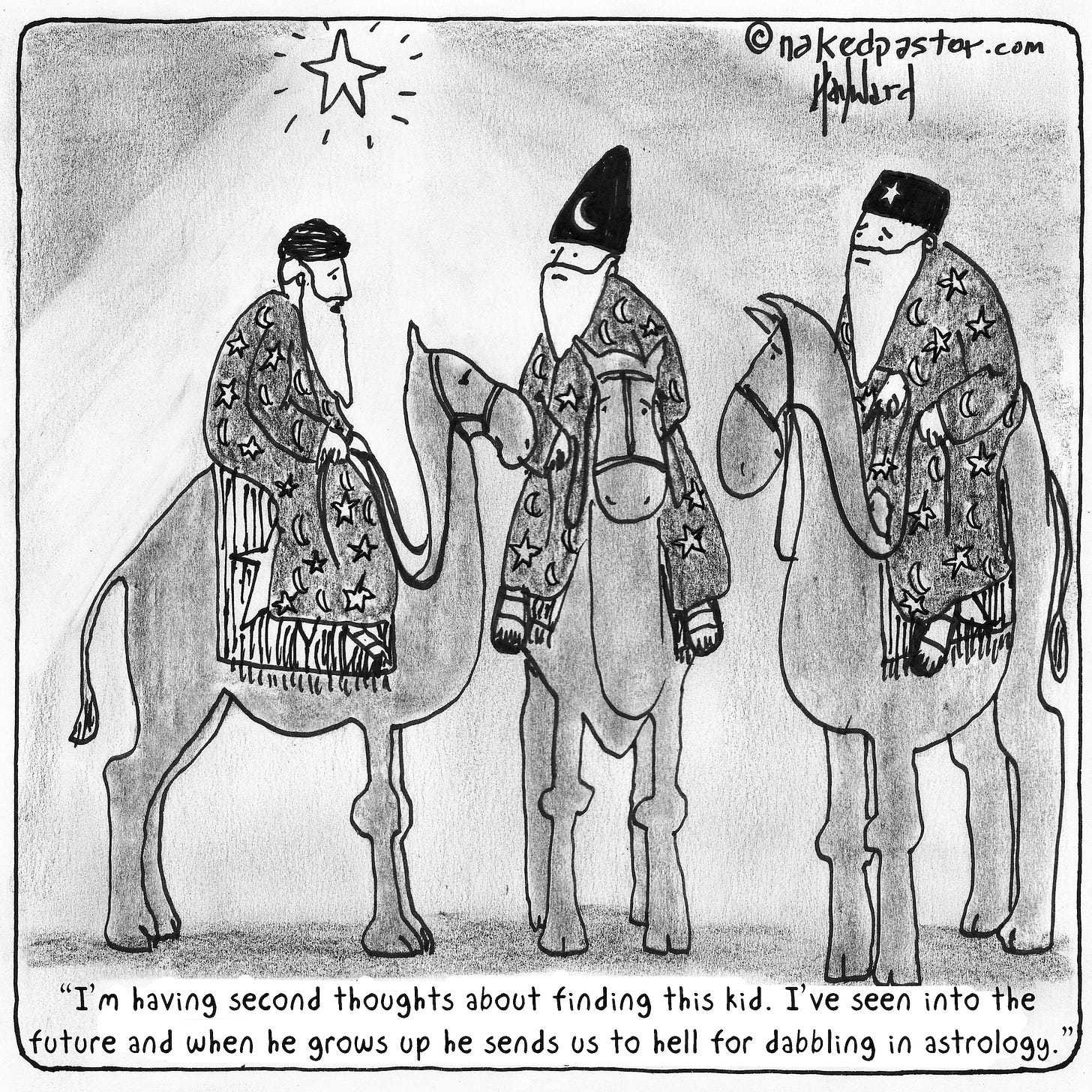

Controversial figures

Interestingly the Magi were controversial figures in the First Century CE. The Book of Acts tells two stories involving Magi3 and both are presented as quite negative.

This seeming contradiction in how the Magi are presented is a good reminder that the New Testament is not a single, coherent document, but rather it's a collection of individual writings penned over several decades, often competing to present their own specific version and vision of truth.

Pliny the Elder, a First Century Roman author, noted that the Magi practiced astrology and had the power to heal. Now you’re beginning to see that the way these powers were perceived in the ancient world seems to have been a matter of perspective. Both magicians and miracle workers performed the same feats, and yet magic was considered bad while miracles were good. As Bart Ehrman has said “one person’s miracle was another person’s magic.”

Curiously Jesus himself was accused of using magic during his ministry and after his death. Much of the evidence comes from the Gospels themselves. He’s accused of working on behalf of an evil spirit called Beelzebub. He physically touches the individuals he heals. He anoints others with a special type of oil4 and instructs his followers how to do the same. And he sometimes uses saliva or spit as part of his healing process. All of these practices could be associated with magicians and sorcerers of the time.

Even better than Magic?

Words often fail us when it comes to understanding certain mystical concepts and powers. I’ve been surprised to learn recently that it’s very common for true mystics to have all sorts of abilities that seem “magical” to us normies.

Let’s just call them mystical powers.

These powers are generally only available to those at the highest levels of consciousness and are used to help others; never for harm or to “show off.”

And so we of course see Jesus (and a few of his followers) demonstrate these mystical powers throughout the New Testament, such as the multiplication (or rather manifestation) of bread and fish to feed large crowds and the many healing stories. This might also inform us why Jesus was so resistant to his mother’s request to turn water into wine.

And why would Jesus use special oils or even saliva to heal? These fluids can be blessed and infused with Divine powers to achieve miraculous results. And even if Jesus himself may not have needed these “tools” for a successful healing, he was teaching his inner circle how to perform these works as well.

Why does Matthew include the Magi?

I believe there were a couple reasons, one being exoteric, or public-facing, and the second being esoteric, or more closely held.

The first likely reason Matthew includes the Magi is to legitimize Jesus as the rightful king of the Judeans. The Magi were often associated with power in the ancient world, serving as advisors to kings and rulers.

The question posed by Matthew’s Magi to King Herod of “Where is the one born King of the Judeans” implies that Herod was not born into kingship, but rather was a mere puppet regime put in place by the Romans.

Marcus Borg and John Dominic Crossan also make the compelling argument that Matthew works hard to present Jesus as the new Moses. There are many parallels between Matthew’s origin story of Jesus and the Exodus origin story of Moses.

Just as Exodus tells of a baby born under an oppressive leader (Pharaoh) who will one day bring freedom to the people who follow him out of Egypt, Jesus is born under the oppression of the Roman Empire and its puppet ruler Herod. Just as Moses will bring freedom and a Promised Land to the Israelites who follow him out of Egypt, Jesus will bring freedom and a new kingdom to all who follow him. Just as Pharaoh orders the execution of all Israelite boys in Egypt, so does Herod order the execution of all boys in Bethlehem.

True Religion

The second, more esoteric reason for Matthew to include the Magi would be to tie Jesus to the true religion that has always existed.5

This is the religion of the mystics, which has remained largely consistent across time, cultures, and religious backgrounds. It is the experience of the Divine as pure love, and our experience of humanity as a sort of school that allows us to grow towards that love.

The mystics of all faith traditions, especially at the highest levels, tend to agree on almost everything, even if their underlying religions have different names for those same things.

And so the inclusion of the Magi, who were mystics and would therefore be known for their ability to perform mystical feats, recalls the “signs” that Moses performed before both Pharaoh and the Israelites. These “signs” in Exodus include turning a staff into a serpent, the healing of leprosy, and turning water to blood; they help establish Moses as not only a legitimate leader, but also a powerful mystic leader. And thus it’s possible Matthew’s intent is to show that the Magi help establish Jesus as a legitimate mystic king.6

An emphasis on Gentiles

Scholars have often pointed out that the Gospel of Matthew has a special focus on Gentiles, and its final lines even command Jesus’s follower to “Go therefore and make disciples of all nations.” The Magi being “from the East” provides continuity with Matthew’s focus that Jesus was here to teach all of humanity.

What about the star that led the Magi to Jesus?

It’s tempting to try and pinpoint the star as having been an historical astronomical event and there are definitely a few candidates. But as astronomer Bradley E Schafer states, such phenomena are, and always have been, quite regular occurrences within most decades of history.

The inclusion of a star could be symbolic, recalling the famous star (actually a comet) that appeared in the sky following the death of Julius Caesar, which was interpreted to imply Caesar’s deification (his becoming divine).

The appearance of this Julian Star would therefore imply Caesar’s adopted son Octavian (soon to be Caesar Augustus) to be the son of God. The motif of the Julian Star was so prevalent in the First Century CE that it appeared consistently on Imperial coinage, even into the 80’s and 90’s CE, when Matthew was written.

And there’s another Julian connection. In Virgil’s epic poem Aeneid, about the founding of Rome, Aeneas is led from the doomed city of Troy to the safety of Italy by Venus, also known as the Morning (and Evening) Star. It is from Aeneas’s lineage that Julius Caesar eventually appears. This story would also be recognized throughout the Empire, and readers of Matthew would recognize the parallels to the Star that led the Magi to Jesus.

And so we see with both these examples the star signifies the author’s belief in the legitimacy of Jesus’s kingship, and perhaps also his connection to the divine.

At the same time, the mystics of two millenia ago do seem to have placed a strong emphasis on the ability to read signs in the night sky. I’m not ruling out the Magi’s ability to have potentially done something of that nature.7 While not my area of expertise, Astrology was once a powerful spiritual component within most all religious traditions.

Was there a prophecy driving the Magi?

Some Christians believe the Magi must’ve studied and interpreted ancient Hebrew scriptures as prophecies that drove them to find the young Jesus. This belief is likely taken from Matthew’s scene in Herod’s court where the chief priests and scribes use scripture to identify Bethlehem as the birthplace.

But I prefer another prophecy.

Some mystics believe the Magi were familiar with the prophecy8 made by the Buddha circa 500 BCE, to his disciple Ananda, stating that a future teacher would appear in 500 years, and that this teacher would be an example of pure enlightenment and teach the pure Dharma.

The Buddha was of course a mystic and one of the great teachers of the True Religion.

So did the Magi really visit Jesus?

Did a group of mystics actually visit the young Jesus of Nazareth?

I could imagine a band of travelling mystics making a visit to Joseph and Mary at some point when Jesus was young. Matthew and Luke record all sorts of mystical “visions” experienced by both Joseph and Mary prior to the birth of Jesus. And it’s believed by many contemporary mystics that Jesus was brought to Egypt not only to escape Herod’s wrath, but more importantly to be nurtured by an Essene community that would begin his preparations for his own future mystical path.9

After all, it seems plausible that Jesus would have been raised in an environment conducive to accessing all those mystical experiences and party tricks. A connection to the Magi (and/or some other ancient mystics like the Essenes) can explain all of this. And taking something that society viewed as bad and using it for good seems like a very Jesus thing to do.

So what do we do with this information?

The Magi were controversial figures in the First Century. The powers that some thought of as Magic was perceived by many to be associated with evil forces, and the Romans even outlawed its use. Jesus himself was accused of being a magician and many of his miracles have similarities with First Century magic.

While Matthew likely includes the Magi to 1) legitimize Jesus as king (while also undermining Herod and possibly the Romans in the process) and 2) demonstrate Jesus’s connection to the Mystical stream, the author’s choice wasn’t without risk of controversy.

And so it seems likely there was a connection between Jesus’s family and a group that some considered miracle workers and others considered magicians.

And perhaps it shows that there was more mysticism baked into First Century Christianity than is commonly understood; an idea we might learn from and should all possibly explore further.

And maybe these mysterious visitors from the East can give us the permission we need to be a little less rigid, a little less certain, and a little more open in our own journey of faith.

“Be grateful for whoever comes, because each has been sent as a guide from beyond.”

~ Rumi

Acknowledgements: much of the research for this post came from the writings of Eric Vanden Eykel and Marcus J Borg & John Dominic Crossan.

Looking for more great content? Jared Stacy wrote an excellent post about the Christmas Star and the Gospel author’s intention of including it in Matthew. Check it out…

One of my favorite mystic teachers insists these actually were their names: Baal-das-Aaussar, Gaspar, and Maharajah Ram. Baal-das-Aaussar was a Bedouin king and astrologer, Gaspar was an Armenian king, and Maharajah Ram was an Indian mystic king. Upon seeing the child Maharajah Ram said, “Ham El Khior,” which means I have seen God, and he was then known as Melchior from that day forward.

The Latin Vulgate, a Latin translation of the Bible produced in 382 CE, was the first to use the word Magi.

Simon Magus and Bar-Jesus. Simon, sometimes referred to as “The Bad Samaritan” by Christians, was quite the figure in antiquity, popping up not only in the book of Acts and some non-canonical Gospels but also in other ancient literature. His popularity persisted into the middle ages and even into today.

doTERRA fans will be disappointed to hear this probably wasn’t Citrus Bliss or Frankincense, but likely kaneh-bosem, which some have recently argued was a cannabis extract. This connection seems a little sensational but still fun to think about.

Even St. Augustine wrote “that which is known as the Christian religion existed among the ancients, and never did not exist.”

More evidence of Jesus being presented by Matthew as the new Moses would be Jesus’s Sermon on the Mount, which is seen as enhancing Moses’s original Ten Commandments.

The primary technology humans will rely on will be spiritual technology. The mystics have documented traveling through time and space and dimensions, and they didn’t even have an iPhone. One day all humans will have these abilities.

Pali Canon and various Mahayana texts

It’s noteworthy that twice the Israelite/Jewish elite were influenced by mystical cultures, first while captive in Egypt and again while captive in Babylon. Both events had major influences on their belief system.

How come you make no mention that the Magi were a class of priests in the Zoroastrian religion? I think that your readers deserve to understand where this terms originated from and how the Zoroastrian religion influenced many Abrahamic religions. I’m happy to provide you more information on this topic but in the meantime I wanted to make sure that you are made aware of this oversight which is think is an important one. Thank you.